About Cornelia Steketee Hulst (1863–1957)

Cornelia Steketee Hulst, Grand Rapids Public Library

On September 1, 1903, Cornelia Steketee Hulst, along with four other women, ran unsuccessfully for the Grand Rapids Library Commission. Governance of the library had been under the control of the Board of Education until 1903, when a charter amendment created a separate library commission elected by popular vote. While no women won seats in the first election, five ran: Mary M. Bryant, Ellen Dean, Alde L. T. Blake, Lois Felker, and Cornelia Steketee Hulst. Steketee Hulst herself received 1,658 votes, putting her in first place among the five female candidates that ran in the first library commission election.

Cornelia Steketee Hulst was born in Grand Rapids on January 16, 1865, to a prominent Grand Rapids family. Her father, a successful businessman, held influential positions in the city, including Supervisor of the First Ward, Revenue Collector for the Fourth District of Michigan, and Vice-Consul to the Netherlands. But Steketee Hulst was not one to rest on her family’s laurels, and she set out to pursue higher education at the University of Michigan, where she studied from 1887 to 1889. There she met her husband Henry Hulst, a physician and University of Michigan graduate. After the wedding, the couple moved to Grand Rapids and Steketee Hulst took up teaching at the city’s Central High School.

Over the course of her thirty-year-long career as an English teacher at Central High School, Steketee Hulst took on pivotal roles in many local, state, and national education advocacy organizations. In 1912, she was elected a vice president of the National Education Association, and in 1913 she became the first woman to ever serve as president of the Michigan Teachers’ Association.

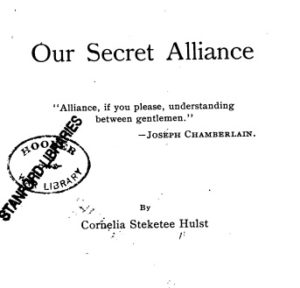

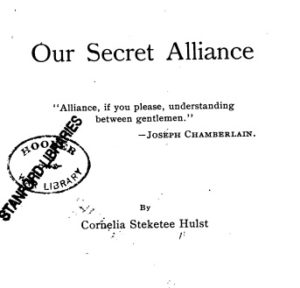

1917, Title Page of Our Secret Alliance by Cornelia Steketee Hulst

In addition to her work in education, Steketee Hulst was also a prolific writer. Most of her works dealt with classical mythology, but she occasionally ventured into contemporary politics. And one such foray landed her in considerable hot water. In 1916, she published “Our Secret Alliance,” an article later published as a short book in 1917 critical of the British government’s motivations for entering the First World War. In this article, Steketee Hulst laid out what she perceived to be a pattern of British imperialism and theorized about the possibility of a secret alliance between Britain and the United States. Although her arguments did not arouse suspicion in 1916 when they were first printed, they became controversial after the United States entered World War I in 1917. What once was just an intriguing theory became, in the eyes of the U.S. government, evidence that Cornelia Steketee Hulst was unpatriotic and therefore not to be trusted. “Our Secret Alliance” was soon banned and, in early 1918, Steketee Hulst faced impassioned calls for her resignation. The case of the unpatriotic Grand Rapids school teacher had become a scandal that aroused ire throughout the entire city.

Steketee Hulst defended herself as best she could. Amid calls for her resignation, she requested a leave of absence that she accompanied with an open letter. In it she claimed that she had, in fact, written the article out of a sense of patriotic duty. She was anti-Imperialist—she insisted—not anti-American.

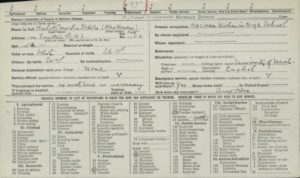

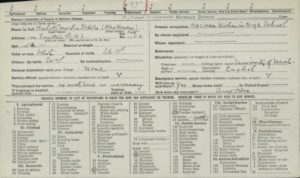

April 27, 1918, Defense Card for Cornelia Steketee Hulst, Grand Rapids Public Library

Newly unemployed and under a cloud of suspicion, Steketee Hulst found it necessary to demonstrate loyalty to her country—even though she had already contributed to the war effort as a state-level committee chair for Michigan’s important Food Production and Marketing Committee of the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense (CND). Very soon after her forced resignation from the public schools, Hulst participated in a massive nationwide registration of women for war work run by the women’s committees of the CND. The Grand Rapids chapter was particularly active and operated many locations where Hulst could have registered. But she chose the busiest and most public: “The Hut” in downtown’s Campau Square. Her choice seems to have been strategic. By registering at such a public venue, Steketee Hulst could ensure that her fellow Grand Rapidians took notice of her support for the war effort.

Steketee Hulst’s attempt to rehabilitate her public image seems to have worked. About a year later, and when the war was over,she engaged in a well-advertised lecture series on ancient myths. Her ordeal seemingly in the past, Cornelia Steketee Hulst would live for forty more years, during which she continued writing and sharing her ideas. Her later publications were far less controversial.

About Cornelia Steketee Hulst (1863–1957)

Cornelia Steketee Hulst, Grand Rapids Public Library

On September 1, 1903, Cornelia Steketee Hulst, along with four other women, ran unsuccessfully for the Grand Rapids Library Commission. Governance of the library had been under the control of the Board of Education until 1903, when a charter amendment created a separate library commission elected by popular vote. While no women won seats in the first election, five ran: Mary M. Bryant, Ellen Dean, Alde L. T. Blake, Lois Felker, and Cornelia Steketee Hulst. Steketee Hulst herself received 1,658 votes, putting her in first place among the five female candidates that ran in the first library commission election.

Cornelia Steketee Hulst was born in Grand Rapids on January 16, 1865, to a prominent Grand Rapids family. Her father, a successful businessman, held influential positions in the city, including Supervisor of the First Ward, Revenue Collector for the Fourth District of Michigan, and Vice-Consul to the Netherlands. But Steketee Hulst was not one to rest on her family’s laurels, and she set out to pursue higher education at the University of Michigan, where she studied from 1887 to 1889. There she met her husband Henry Hulst, a physician and University of Michigan graduate. After the wedding, the couple moved to Grand Rapids and Steketee Hulst took up teaching at the city’s Central High School.

Over the course of her thirty-year-long career as an English teacher at Central High School, Steketee Hulst took on pivotal roles in many local, state, and national education advocacy organizations. In 1912, she was elected a vice president of the National Education Association, and in 1913 she became the first woman to ever serve as president of the Michigan Teachers’ Association.

1917, Title Page of Our Secret Alliance by Cornelia Steketee Hulst

In addition to her work in education, Steketee Hulst was also a prolific writer. Most of her works dealt with classical mythology, but she occasionally ventured into contemporary politics. And one such foray landed her in considerable hot water. In 1916, she published “Our Secret Alliance,” an article later published as a short book in 1917 critical of the British government’s motivations for entering the First World War. In this article, Steketee Hulst laid out what she perceived to be a pattern of British imperialism and theorized about the possibility of a secret alliance between Britain and the United States. Although her arguments did not arouse suspicion in 1916 when they were first printed, they became controversial after the United States entered World War I in 1917. What once was just an intriguing theory became, in the eyes of the U.S. government, evidence that Cornelia Steketee Hulst was unpatriotic and therefore not to be trusted. “Our Secret Alliance” was soon banned and, in early 1918, Steketee Hulst faced impassioned calls for her resignation. The case of the unpatriotic Grand Rapids school teacher had become a scandal that aroused ire throughout the entire city.

Steketee Hulst defended herself as best she could. Amid calls for her resignation, she requested a leave of absence that she accompanied with an open letter. In it she claimed that she had, in fact, written the article out of a sense of patriotic duty. She was anti-Imperialist—she insisted—not anti-American.

April 27, 1918, Defense Card for Cornelia Steketee Hulst, Grand Rapids Public Library

Newly unemployed and under a cloud of suspicion, Steketee Hulst found it necessary to demonstrate loyalty to her country—even though she had already contributed to the war effort as a state-level committee chair for Michigan’s important Food Production and Marketing Committee of the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense (CND). Very soon after her forced resignation from the public schools, Hulst participated in a massive nationwide registration of women for war work run by the women’s committees of the CND. The Grand Rapids chapter was particularly active and operated many locations where Hulst could have registered. But she chose the busiest and most public: “The Hut” in downtown’s Campau Square. Her choice seems to have been strategic. By registering at such a public venue, Steketee Hulst could ensure that her fellow Grand Rapidians took notice of her support for the war effort.

Steketee Hulst’s attempt to rehabilitate her public image seems to have worked. About a year later, and when the war was over,she engaged in a well-advertised lecture series on ancient myths. Her ordeal seemingly in the past, Cornelia Steketee Hulst would live for forty more years, during which she continued writing and sharing her ideas. Her later publications were far less controversial.

Campaign Information

Political Office: Library Commission

Election Year: 1903

Party Affiliation: Nonpartisan race

Elected: No

Biographical Information

Full Name: Cornelia Steketee Hulst

Life Dates: 1863–September 24, 1957

Birthplace: Grand Rapids, Michigan

Marital Status: Married

Occupation: English Teacher, Author

Party Affiliation: Unknown

Social Reform Activism: Education, Civic Reform, Women’s Clubs

Sources

Defense card for Cornelia Steketee Hulst. April 27, 1918, 174-9-805. Women’s Defense Cards Collection. Grand Rapids Public Library Digital Collections, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“Mrs. Hulst Asks Leave from Duty for School Year: Makes Request Tuesday and Accompanies it with Open Letter.” Grand Rapids Press, March 26, 1918.

“Mrs. Hulst Given Leave from Duty Without Salary: Teacher Whose Loyalty Was Questioned Not to Get New Contract.” Grand Rapids Press, April 2, 1918.

“Mrs. Hulst to Lecture.” Grand Rapids Press, April 19, 1919.

“Mrs. Hulst is Chosen to Head State Teachers: Grand Rapids Instructor is First Woman to be Accorded the Honor by Association.” Grand Rapids Press, October 31, 1913.

“School Trustees ‘Informal’ On Mrs. Hulst Case.” Grand Rapids Press, March 21, 1918.

Steketee Hulst, Cornelia. Our Secret Alliance. Chicago: League to Ensure International Justice, 1917.

“Teachers Talking of Open Revolt: Eastern Members of National Association Bitter Over Defeat of Miss Strachan: Urging Separate Branch: Mrs. Hulst of Grand Rapids is Chosen Vice President at Chicago Convention.” Grand Rapids Press, July 11, 1912.

“Trustees Led the Battle: Library Commissioners Took Back Seat at the Polls.” Grand Rapids Herald, September 2, 1903.

Woman’s Who’s Who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915. New York: American Commonwealth Company, 1914.